In some ways we’ve come a long way since the 1930s, and in others we really haven’t.

In case you missed it, next week a Dartmoor landowner is taking the National Park Authority to court to try and end wild camping there.

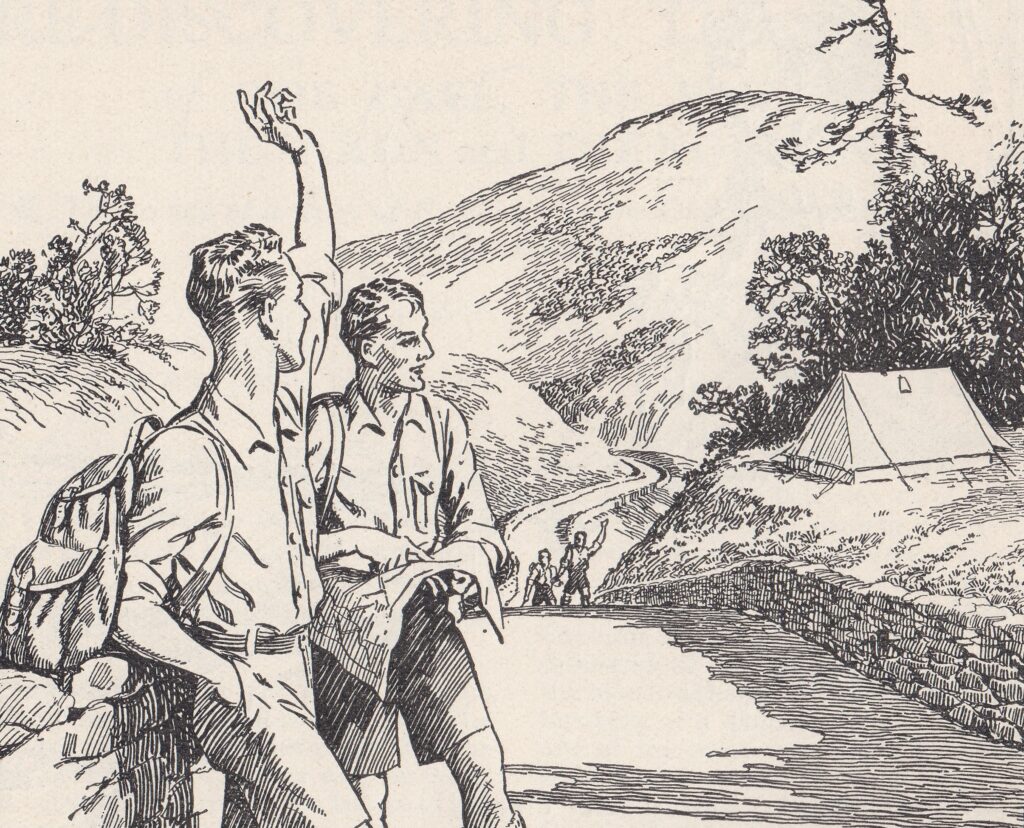

Dartmoor is the only place in England where wild camping is currently legal under national park byelaws, and generations have learned to love the outdoors with the rare freedom to roam open country and put their tent up at the end of the day.

Post-lockdown ‘fly-camping’

The landowner – an investment manager who bought his 4,000-acre shooting estate 11 years ago – asserts that camping is linked to littering, poaching and wildfires. It’s true that the pandemic-era craze for ‘fly-camping’ was pretty horrid, but many park authorities took steps to try and control it at the time, and it’s mostly petered out by now. A lot of us have been wild camping (both legally and illegally) for decades, and when we leave a pitch you’d honestly never know we’d been there.

All the anti-social behaviour he mentions is illegal anyway, and the national park has found no evidence that conventional wild camping has lasting negative effects on the landscape. Data for Devon and Somerset (cited in this article) suggests that far more fire service call-outs last year were due to land management than camping. That’s not to criticise those who work in the countryside – accidents happen and it just puts the single call-out for a camping stove fire into perspective.

I tend to think that the more you ban people from the land, the less they will know or care about it. It’s a well-worn refrain that townies don’t understand the countryside, but if you don’t let them explore it and experience it, how can they ever hope to?

The many definitions of freedom

And that’s before you consider the life-enriching qualities of days and nights spent under the sky. We’re built for the outdoors. The exercise and space to think and explore without limits, that counterpoint between vastness and tiny details, the discomfort and tiredness and wonder of it all. You’re alive in a way that you simply never will be in the world of central heating and screens.

Times spent in the outdoors have been among the best of my life, and it’s easy to forget that in an alternative universe I might never have had any of them. They are the result of a dogged campaign for outdoor access rights that has been going on for nearly a century.

Of course, freedom means a million different things depending on who you are. As Sebastian Junger says in his book on the subject, at its most basic level, freedom is life without threat, and if you want that then you usually have to trade some other freedoms for it.

But that’s not what this is. In the case of outdoor access, the people who routinely work that rough edge where freedom meets risk are the mountain rescue teams. They might grumble about people setting off up Snowdon ‘dressed for the supermarket‘, but you don’t catch them campaigning for reduced access to the outdoors.

I suspect most resistance to outdoor access comes down to jealousy. It’s the same sour feeling that springs up in me when I go down to ‘my’ beach on a summer evening and find twenty camper vans parked there. We don’t like to share, and we don’t like to feel like someone else is having more fun than us – especially if they’re aren’t paying for it.

Live and let live

Outdoor access doesn’t have to be adversarial. I don’t think farmers and gamekeepers are the enemy. They’re often very friendly, and my side of the deal is to leave their stock, game and property alone (more the point, to make sure my dog does too). But I do think it’s a hideous idea that the only people who should be allowed to enjoy the country we live in are the super-rich and their employees.

I know there’s much worse going on elsewhere in the world, but that doesn’t mean our own freedoms aren’t important (cut with a corresponding degree of responsibility, which of course is the contentious bit). This case on Dartmoor is a reminder that there’s always someone looking to take those freedoms away.

Five pointers for wild camping

- Arrive late, leave early. Be subtle.

- Don’t leave anything behind, and don’t damage anything.

- The two things that landowners are usually most worried about are fire and dogs. Be extremely careful with both. Fires are usually off the menu unless you can completely obliterate it afterwards (for example, on a sandy beach).

- In general, don’t pitch up in a place where loads of other people have obviously camped.

- Walking five minutes from a car park to a spot you found on a Facebook ‘wild camping’ page is not wild camping. And there’s probably human shit lying around.