In 1847, When Essex-born John Christopher Atkinson put it about that he’d been asked to become vicar of the remote North Yorkshire village of Danby, one wag declared: ‘Why, Danby was not found out when they sent Bonaparte to St Helena; or else they never would have taken the trouble to send him all the way there!’

The auspices were not favourable. The church was said to be at least a mile from the nearest villagers, and the local landowner, Viscount Downe, expressed some reservations about the incumbent clergyman, noting that the man was not ‘famed for strength of body, nor energy of mind and purpose’. This turned out to be something of an understatement. On arrival, the 33-year-old Atkinson found the church rotting from the inside out. The woodworm-pocked altar doubled up as a picnic table for the Sunday school teachers, the font was a ‘paltry slop-basin’, and the place reeked of baccy since the parish clerk liked to perch in the alcove by the west window and smoke his pipe. As for the minister, his attendance at church was rather poorer than that of his meagre flock, and he confided peevishly in Atkinson that his parishioners had ‘not been very thoughtful or considerate about me’, on account of their incessant requests for him to baptize and christen their children.

More than half a century later, Canon Atkinson died at Danby vicarage, having carved out a remarkable life for himself in his unpromising moorland patch. A renaissance man to his core, he was an archaeologist, a philologist, a naturalist, a geologist, a historian and a folklorist. Most significantly, he assiduously documented the customs, rituals, language and mythology of a folk culture which was even then in terminal decline, and wrote several books, of which Forty Years in a Moorland Parish (1891) is the most famous.

It’s out of print, but the text is available online, and a while back I tracked down a handsome and dilapidated old leather-bound copy, once the property of Liverpool College*. It’s a July 1891 special edition with maps and photo plates by Frank Meadow Sutcliffe, and the colour of the leather stains your hands as you read. As an object, it is most pleasing, but the text itself is even more enjoyable. It’s written with an endearing lightness, humour and enthusiasm, and Atkinson’s affection for rural Yorkshire and its people is infectious. What’s more, his geographical descriptions and maps are very precise, to such an extent that I’ve already been able to plot some Atkinson walks out on the moors.

One of his great passions was language (back in 1868 he’d published A Glossary of the Cleveland Dialect), and Forty Years in a Moorland Parish contains all kinds of delicious old words that have long since fallen out of use. Indeed, many of them had disappeared by the time the book was published, so Atkinson helpfully provides translations. Here are some of my favourites:

Arvel – an adjective referring to a specific celebration (much like the word ‘bridal’). In this case it relates to a celebration of inheritance. ‘At arvel … feasts … when heirs drank themselves into their fathers’ lands, there was great mirth and jollity, and much eating and hard drinking of mead and fresh-brewed ale.’

Backbearaways – bats

Gabble-ratchet – a yelping sound at night, like the baying of hounds. Probably just caused by flocks of geese flying overhead, but generally interpreted as an omen of impending death.

Gam’some – frolicsome, often used of ‘kitlins’ (kittens).

Gorpins – fledglings

Moudiwarps – moles

Pricky-back otchins – hedgehogs

Swipple – a lovely onomatopoeic word for the striking part of a flail, used for threshing.

Warsle – wrestle

Yabble – well-to-do

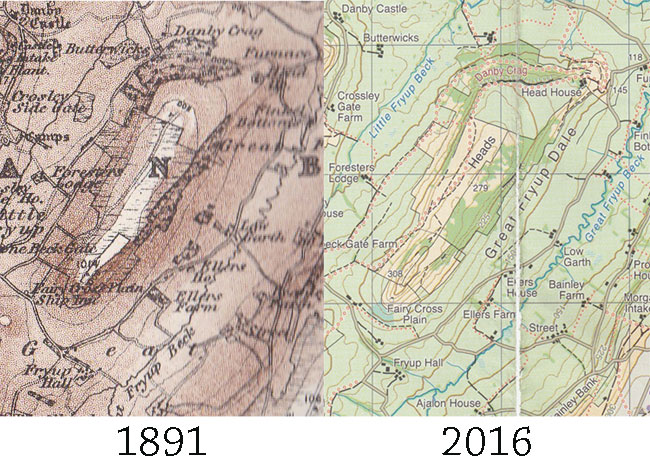

There are undoubtedly more blog posts to be had out of Canon Atkinson, and in the next couple of weeks I’m hoping to have a snoop around some of the places mentioned in his book. It’s been over a century, but North Yorkshire hasn’t changed all that much, as you can see from this side-by-side comparison of Atkinson’s map and my modern Harvey one. The Ship Inn may have disappeared, but the Fairy Cross Plain where children used to run round the fairy rings (though never nine times, so as not to give the fairies the power to steal them away) is still there, awaiting my inspection.

Sadly, when I pass Danby Beacon I’m unlikely to marvel at the sight of a white-tailed eagle, as he did, since they’ve been extinct in England for a century.

*Some former – presumably long-dead – student at this institution has folded over the page corner to mark a passage detailing an old wedding ritual, in which drunken male wedding guests competed in a race from the churchyard to the bride’s front door. The winner was awarded not only the bride’s garter, but also the privilege of removing it. I’d love to know why this was of interest.